This House Has Seen It All

Past Owners Include an Early Denver Developer, a Lawyer Who Stood Up To The KKK, and a Famed Colorado Mountaineer and Inventor. Now, Their Old Park Hill Home Is an Historic Landmark.

By Cara DeGette

Editor, GPHN

Risky business, lost fortunes made again; midnight car chases and threats of violence from the Ku Klux Klan; snowshoe inventions and climbing pitons hammered into the walls.

“This place has seen it all, right here,” George Dennis says, of his house, which stands prominently at the northeast corner of 26th and Clermont.

Built in 1911, the architecture is distinctive Mission Revival style with Craftsman elements, including curvilinear parapets, large windows for light and massive timbers at the eaves.

It was originally designed as a “Tuberculosis house,” with a sleeping porch, (sometimes called a “cure porch”) that encouraged the circulation of fresh air to help combat the disease that brought so many to Denver at the turn of the last century. All the bedroom windows open to a 15-window solarium. The main floor is 2,581 square feet, with another 2,581 square feet of unfinished basement with 9-foot high ceilings and detached garage.

Since Dennis and his wife Beverly bought the house in 2008, they have painstakingly restored what was an uninhabitable run-down mess to its original glory. In late January, after an extensive process, they convinced the Denver City Council to designate it as an historic landmark. That means, as George Dennis puts it, “it makes it extremely difficult to demolish it; it would practically take an act of Congress.”

It wasn’t just the hard, tedious work of restoration that inspired the Dennises to seek landmark preservation for the home, which they have named the Kittredge-Ginsberg-Forrest House (KGF for short). It was also the history.

Specifically, the remarkable stories – which the Dennises pieced together during years of archival research – of three past owners of the house, whose contributions were significant to early Denver and Colorado in vastly different ways.

Imagine these ghosts strolling the corridors of your house:

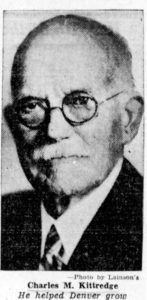

• Charles Marble Kittredge, a banker, developer and visionary whose influence on early Denver helped establish it as a city of substance;

• Attorney Charles Ginsberg, who conducted a personal and public crusade against the Ku Klux Klan during Denver’s period of social discord, corruption and violence during the 1920s;

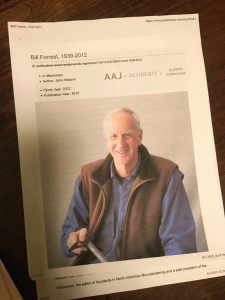

• Mountaineer Bill Forrest, whose inventions inspired climbers to conquer sheer rock walls and who helped establish Colorado’s reputation as an outdoor wonderland.

On Jan. 27 the Denver City Council voted unanimously to approve historic landmark designation for the KGF house. Councilwoman Amanda Sandoval thanked the Dennises for their efforts and said she is encouraging her constituents to follow suit.

“Often this is the only protection we have, the only way we won’t [demolish] the history of Denver,” Sandoval said. “Tell your neighbors we welcome these proactive designations.”

The Dennises hope their efforts inspire others. “Many of us in Park Hill are concerned over the degradation of the neighborhood’s appearance and ambience from a charming, inclusive, middle class community to something entirely different,” George Dennis said.

“There are so many cool houses in Park Hill – who knows what ghosts they got?” he continued. “Landmarking, one house at a time, is a direct way you can help preserve the neighborhood’s brick-and-mortar character, and honor the hard-working people who came before us.”

Making it habitable

The house, at 4431 E. 26th Ave., is the Dennises seventh remodel project. When they bought it 12 years ago, they had no idea of its history or past occupants. They just knew they had a wingding of a restoration project on their hands.

“It was a wreck,” Dennis said. The house had been foreclosed three times. All the light fixtures were gone, the doors were gone. The first many months were spent just making it habitable.

Over subsequent years, they’ve tackled a multitude of projects to restore the house to its original. They removed the pitons that former occupant Bill Forrest had hammered into the wall outside and in the basement. They removed an 8-foot wooden hot tub that Forrest had installed in the solarium, and they reused the California Redwood to rebuild the front porch.

They replaced the damaged sashes of the large front and side windows. Each piece of original stained glass was cleaned by hand. The fence around the property is only six years old, but its pattern is from a 1911 Sears catalog. They are currently trying to figure out how to remove the heavy nicotine stains on the dining room ceiling, doors and walls – a likely relic from cigar-chomping former occupant Charles Ginsberg.

While they were applying some serious elbow grease, the couple was also doing what they’ve always done with their old homes: researching past inhabitants. They searched property records, made trips to the Denver Public Library’s Western History department, employed online search databases. Their findings were a veritable treasure-trove. (See sidebar below.)

‘We’re the custodians’

The only alteration the Dennises made to the home’s exterior was to install solar panels. It was the presence of the solar panels that made the couple initially doubtful they could successfully attain landmark preservation status. However, George Dennis credits city planner Jenny Buddenborg, as well as former Denver landmark preservation commissioner Amy Zimmer, who were enthusiastic and helped guide the couple through the process.

They chose to honor the three former occupants, by naming the home the Kittredge-Ginsberg-Forrest House. “We’re the custodians, not the makers of history,” Dennis said. The ultimate test for preservationists, he says, is whether the original owners would be able to recognize their old house.

“If these guys were to come back, I’d like them to take a look around and say, ‘looking pretty good, looking pretty good.’ ”

At Home, at 26th And Clermont

Three Men Who Made Their Mark On Denver

Editor’s Note: The following biographies of Charles Kittredge, Charles Ginsberg and Bill Forrest were extensively researched and written by Beverly and George Dennis. They were included in the couple’s application for Historic Landmark Designation and are condensed here for space.

Charles Kittredge – 1858-1940, Resident 1911-1915

In 1884, Charles Kittredge, a banker from Alma, Kansas, arrived in Colorado, ostensibly to recoup his health. He and a partner, R.H. McMann, opened the McMann and Kittredge bank on lower Fifteenth Street. A trained engineer as well as a financier, Kittredge, with his father, built the Kittredge Building at the corner of 16th and Glenarm in 1891. The building is now on the National Register of Historic Places and remains prime office space overseeing the 16th Street Mall.

That same year, Kittredge built his opulent residence, the Kittredge Castle, at 6925 E. 8th Ave. The massive stone castle was filled with elaborate carvings, furniture, galleries and art (the dining room alone seated 100). The silver market crash of 1893 hit the Kittredges hard; they ultimately lost their building downtown, and were forced to sell the castle (which was demolished in 1956).

By 1908, Charles Kittredge was vice president and manager of Park Hill Heights Realty Company. In 1911 he built and moved into the house at 26th and Clermont with his wife Anna and their son, Charles Marble Kittredge, Jr. Charles Senior continued to plan and build in Park Hill, and helped develop what is now the Montclair and East Colfax neighborhoods (he was the first to build bungalow-style houses and also built many houses designed for tuberculosis patients). He was friends and contemporaries with other early well-known Colorado pioneers such as Horace Tabor, David Moffatt and Baron von Richtofen (who once asked Charles to loan him 50 dollars to make his payroll).

Ultimately, Kittredge developed and moved to his own mountain subdivision – what is now the town of Kittredge, near Evergreen.

Charles Ginsberg 1894-1875, Resident 1920-1929

Charles Ginsberg was born on a farm outside of Golden and graduated with a law degree from the University of Denver in 1914. He was heavily involved in Democratic politics, which brought him into contact, and conflict, with the Ku Klux Klan.

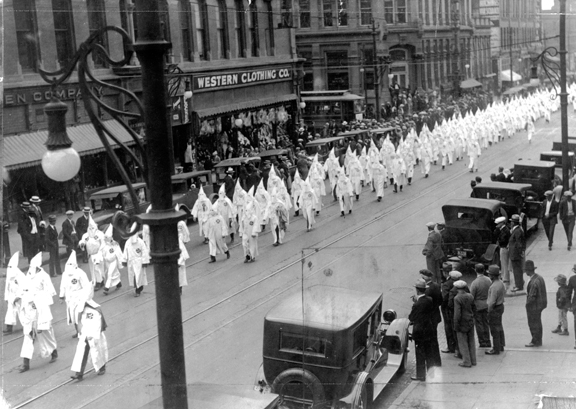

In the 1920s, the period that Ginsberg owned and lived in KGF House, the Klan was becoming all-powerful in Colorado. Among active Klan members at the time were the governor, both U.S. senators from Colorado, the mayor of Denver, many judges, and thereby a host of political appointees.

The state and city government’s extensive efforts to marginalize Catholics, Jews and African Americans at that period are well documented. Only a handful of members of those target communities spoke out against the corruption, violence and legal impunity of the Klan. But Ginsberg, who was Jewish, was one of the most outspoken critics of the Klan and the government it controlled. In editorials, public speeches and political action, Ginsberg “was a true hero of his day fighting the Klan.”

In 1963, a DU grad student recorded Ginsberg in an interview about the years between 1921 and 1925, when Klan activity was at its peak and Ginsberg was a “constant thorn in their plans.” Ginsberg described an historic debate between himself and Klan zealot, national spokesperson and minister of Denver’s Highlands Christian Church, the Rev. William Oeschger. It was the first event at the newly completed Mackey Auditorium in Boulder. Nearly 1,000 spectators were there, comprised mainly of the Klan faithful. The next day, the Boulder Camera reported Ginsberg “wiped the floor” with Oeschger. “Ginsberg’s arguments and rhetorical panache won the day, exposing, embarrassing and holding the Klan accountable for its secrecy, racism, and undemocratic nature,” according to the Camera.

Soon after the debate, the Klan made an attempt on Ginsberg’s life. In the interview, he described a harrowing midnight automobile chase across City Park, as he was pursued by an open car full of Klansmen. Ginsberg led his pursuers to the police station at Colfax and York, where he recognized the desk sergeant as another Klansman who naturally refused to lend him a gun. Cornered, Ginsberg picked up the phone and dictated his story to the night editor at the Denver Post, asking him to run the story should anything happen to him on his way home to 26th and Clermont. Ginsberg made it home.

Note: In their application for historic designation, the Dennises included this observation: “In today’s national climate of hate speech, nativism, divisiveness and racial violence, the parallels with the time of Charles Ginsberg nearly 100 years ago are both astonishing and frightening … It is good to know that back then, just as now, there were a few people who fearlessly spoke truth to power, defended the defenseless and demonstrated the courage that Charles Ginsberg, Esq. had in 1920s Denver.”

William “Bill” Forrest 1939-2012, Owner and resident 1971-1998

Mountaineer, mentor, inventor and businessman Bill Forrest was born in Glendale, Calif. and grew up in Salt Lake City, Utah. Joining the Army in 1957, Forrest was sent to Germany where he took up, then mastered, alpine technical climbing.

By 1968 he had established Forrest Mountaineering Ltd. in Colorado. In 1970 he mounted the first solo ascent of the east face of Long’s Peak. In 1971 he purchased KGF House and discovered his passion for inventing and improving mountaineering gear in the basement of a huge, old rambling house in Denver that he ran as a boarding house and think tank for climbers. With climbing partner Kris Walker, Forrest put up the first ascent of the Painted Wall in the Black Canyon of the Gunnison in 1972. It took nine days to establish the 26-pitch route on the 2,500-foot cliff, Colorado’s tallest. It was also the first trial by fire for his newly designed wall hammer suited to driving in and removing pitons from existing cracks.

Bill Forrest was a proponent of natural climbing. That is, using the natural cracks and features of the rock to anchor ropes and gear instead of damaging it by hammering in protection devices. Mountain Safety Research (MSR) first became aware of Bill Forrest in 1994 when he showed the company his radically new snowshoe … the “Denali,” which ultimately became the company’s best-selling snowshoe.

In 1998 Forrest sold KGF House and moved to Salida for better access to the mountains. When he retired in 2010, Forrest had more than 100 products on the market and 17 patents to his credit. He died of a heart attack in 2012 on Monarch Pass, while snowshoeing with his wife.

THOSE OLD BONES

How To Sleuth Your Home’s Past Occupants; Resources For Seeking Historic Designation

Digging up the past isn’t as complicated as it may seem. But it can be time consuming.

Some property records and chain of titles are available via the Denver Assessor’s website. However, those records often do not date very far back. A trip to the assessor’s office, at City Hall downtown, can help turn up a complete chain of ownership. The Denver Clerk and Recorder also has published a limited number of real estate and other historical documents online.

Colorado and Denver historians Tom Noel and Phil Goodstein have written expansively about the original owners of Denver’s old homes. Noel’s 2002 book, The Park Hill Neighborhood, includes histories and descriptions of many of the neighborhood’s most prominent houses and their owners. Goodstein’s book, Park Hill Promise, provides an extensive inventory of the neighborhood’s original homes.

The Denver Public Library Western History and Genealogy Department, in the main DPL branch downtown, is an excellent resource. There, you can research people who once called your home, home, as well as getting the lowdown on other notable Denver and Colorado pioneers and trailblazers. The research library at History Colorado, also downtown, is also a great resource, as is anscestry.com.

The organization Historic Denver is a treasure-trove of information for helping property owners pursue landmark historic designation to forever protect old homes and buildings from the bulldozers. Historic Denver was formed in 1970 when a group of people organized to save the historic Molly Brown House from demolition.

“Historic designation is one method of ensuring that changes to a neighborhood occur thoughtfully, preserving the fabric of a neighborhood that people love — homes with history, vital dwellings that preserve the past — while acknowledging modern lifestyles,” according to Historic Denver’s website.

Generally, homes must meet at least one of three criteria for historic preservation: The structures are architecturally distinct, geographically prominent, and/or past owners have some historical influence.

Historic Denver notes that restoring or rehabilitating historic structures often requires planning, a love of challenges, and money. Historic properties can be eligible for preservation tax credits and other incentives, including restoration grants. Read more about funding sources, and a general guide to frequently asked questions, at historicdenver.org/resources/.

If you are interested in pursuing historic designation, contact Shannon Stage at 303-534-5288, ext. 6.

— Cara DeGette