Park Hill’s Pandemic Past (Part 1)

Reflections Of The Spanish Flu In Denver and Colorado

By Stephen J. Leonard

For the GPHN

On Sept. 27, 1918, Park Hill secured a dubious place in Denver’s history when Blanche Kennedy, residing at 2070 Birch St., became the city’s first reported victim of the influenza pandemic that was then ravaging the world.

Kennedy¸ a 21-year-old University of Denver student, supposedly contracted the disease in Chicago, and brought it home. Dr. J. C. Weld, Kennedy’s physician who lived just blocks away, at 2349 Bellaire St., confirmed that she had died from influenza.

Dr. William H. Sharpley, the city’s manager of health, put the Kennedy’s house under quarantine. He told Denver’s Rocky Mountain News of Sept. 28, 1918, that he was “confident that the death of Miss Kennedy will not be responsible for any cases in this city.”

Sharpley was overly optimistic. Kennedy was likely not the only Denverite infected with the flu in late September. The disease had been spreading across the U.S. for more than a month. Kennedy’s death was to be the first of more than 1,500 Denver residents who succumbed to the flu and its complications, about six-tenths of one percent of the city’s approximately 250,000 people. Statewide the numbers were even more appalling. More than 7,750 people perished – about eight-tenths of one percent of the state’s population.

Nationwide, between 500,000 and 675,000 Americans died – more than all the American deaths in all the wars of the 20th and 21st centuries. Millions more were sickened by the plague.

Most of Denver’s and Colorado’s deaths occurred in 120 days between late September 1918 and late January 1919. The numbers overwhelmed hospitals and communities’ ability to cope with the fast-moving nightmare.

The three C’s

For more than a century scholars have been analyzing the 1918 pandemic, known as the “Spanish Flu” because it was mistakenly believed to have originated in Spain.

Today some scientists think its precursors date back to 1915, and some suggest that a version of it cropped up near Fort Riley in Kansas in the spring of 1918. At the time, people called it the grippe, a type of severe influenza that had ravaged the world in the late 1880s and 1890s. Denver mayor Robert W. Speer, now remembered for beautifying the city, succumbed to pneumonia on May 14, 1918 after a bout of the grippe.

The virus spread to Europe by soldiers bound for French battlefields, where it mutated into a more virulent form.

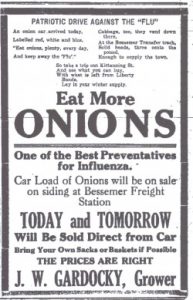

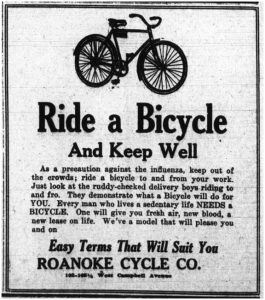

The flu baffled doctors. No optical microscope could reveal it; no known vaccine could prevent it. Poppycock preventatives and remedies flowed freely – eat onions, take Pleasant Purgative Pellets, enjoy a hot mustard footbath, carry an acorn, avoid tight shoes and gloves.

Other suggestions appeared sensible – take deep breaths of pure air and practice the three C’s: “clean mouth, clean heart and clean clothes.”

On Nov. 5, 1918, the Rocky Mountain News urged readers to vote Republican “and you need have no fear of the flu.”

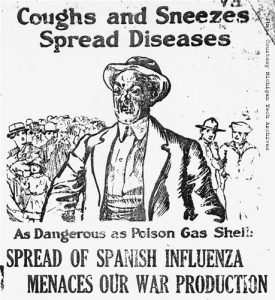

Sharpley and others familiar with highly communicable respiratory diseases such as tuberculosis understood that coughing and sneezing probably spread the malady. They recognized that people crowded into close quarters were at risk. Unfortunately, for a time, they thought that outside air was good air and hence saw no harm in large outdoor gatherings. An estimated 40,000 people packed Cheesman Park on Saturday, Oct. 5 to view a World War I battle aircraft featured as part of the federal government’s effort to sell War Bonds.

Message to moviegoers

In the wake of Blanche Kennedy’s death, Sharpley asked theater owners to flash a message on their movie screens: “Spanish Influenza is conveyed by coughing, sneezing and spitting.” That admonition demonstrated the futility of closing the barn door after the horse was out.

Denver had known about the flu and its rapid spread mainly from East Coast locations, particularly Army camps, for more than a month. On Sept. 21, solider-trainees at the University of Colorado in Boulder were reported ill. Four days later 75 sick CU students were quarantined in fraternity houses. By the time the flu reached Denver it had killed more than 1,000 in Boston.

Increasing numbers of deaths in early October caught the public’s attention. Blanche Kennedy’s brother, William R. Kennedy, also of 2070 Birch, died on Saturday, Oct. 5. That evening the city’s Board of Health ordered all schools, theaters, churches, and places of amusement to close as of 11 a.m. on Sunday, Oct. 6. Police stopped picking up vagrants and Sharpley dispatched inspectors to make sure soda fountain employees washed their glasses in hot water.

Some citizens voluntarily started wearing masks in October. When Sharpley learned that owners of a garment factory would not provide heat for their 60 women employees he ordered the shop closed. Justifying his interference with free enterprise, he explained, “These are epidemic times.”

Some citizens voluntarily started wearing masks in October. When Sharpley learned that owners of a garment factory would not provide heat for their 60 women employees he ordered the shop closed. Justifying his interference with free enterprise, he explained, “These are epidemic times.”

Still, many businesses remained open, outdoor meetings were allowed, and some refused to comply with the Board of Health’s restrictions. Socialite Bulkley Wells hosted a party. Wealthy Genevieve Chandler Phipps decamped to her spacious, mountain estate, Greystone, in Upper Bear Creek Canyon west of Evergreen, where she partied and breathed the pure air.

Under deeps of darkness

Deaths and widespread sickness continued. On Oct. 15 officials forbade all meetings – indoors or out. A few days later the Board of Health informed all businesses they must close by 6 p.m. Theater owners initially supported the restrictions, but within a few weeks they were complaining about lost business. Under pressure, Sharpley lifted the ban on public gatherings on Nov. 11, 1918. Having the rule in place that day could not have stopped the tens of thousands of people who took to the streets to celebrate the armistice that ended World War I.

Katherine Anne Porter, destined to become one of the nation’s most acclaimed writers, was a reporter for the Rocky Mountain News in 1918 when she contracted the flu. She ran a fever of 105 degrees for nine days. In her 1939 short novel, Pale Horse, Pale Rider, her fictional character, Miranda, gives a glimpse of Porter’s own close encounter with death:

Silenced, she sank easily through deeps under deeps of darkness until she lay like a stone at the farthest bottom of life, knowing herself to be blind, deaf, speechless, no longer aware of the members of her own body, entirely withdrawn from all human concerns, yet alive with a peculiar lucidity and coherence; all notions of the mind, the reasonable inquiries of doubt, all ties of blood and the desires of the heart, dissolved and fell away from her . . .

By Nov. 21, the city had tallied nearly 500 deaths. Sharpley then predicted: “I believe that by the end of a week, Denver’s death rate will be normal.” As was the case in September, his rosy outlook was ill founded.

This is Part I of a series on the 1918 influenza pandemic – a sad slice of history, which is perhaps instructive. Its author, Stephen J. Leonard, is a professor of history at Metropolitan State University of Denver and holds a doctorate in history. He lives in Park Hill. Both his mother and father survived the 1918 flu. Had that not been so, it goes without saying he would not have written this piece. This account draws heavily on Leonard’s 1989 essay, The 1918 Influenza Epidemic in Denver and Colorado in Essays and Monographs in Colorado History: Essays Number 9, 1989, published by the Colorado Historical Society (now History Colorado). The second installment of this series will appear next month.

This is Part I of a series on the 1918 influenza pandemic – a sad slice of history, which is perhaps instructive. Its author, Stephen J. Leonard, is a professor of history at Metropolitan State University of Denver and holds a doctorate in history. He lives in Park Hill. Both his mother and father survived the 1918 flu. Had that not been so, it goes without saying he would not have written this piece. This account draws heavily on Leonard’s 1989 essay, The 1918 Influenza Epidemic in Denver and Colorado in Essays and Monographs in Colorado History: Essays Number 9, 1989, published by the Colorado Historical Society (now History Colorado). The second installment of this series will appear next month.