‘Fight for Fifteen’ Campaign Pushes For Living Wages

More Colorado Workers Sliding Into Poverty

The growing movement to improve the wages of low-income workers – in Denver and nationwide – could benefit the entire economy.

“Up to one-third of all U.S. workers are in low-wage jobs, not just in fast food, but home health care and other service industries,” says Park Hill clergyman Daniel Klawitter, deacon in the Rocky Mountain Conference of the United Methodist Church and the former head of Interfaith Worker Justice. “Far too many of these employees who work full time are dependent on public assistance, and that is a cost we all pay, one way or another.

“A living wage is part of the larger struggle to address historic income inequality in the U.S.”

Chanting “Get up, get down, fast food workers feed this town,” groups of as many as 200 have recently rallied at McDonald’s restaurants in Denver. Similar protests have taken place in New York City, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, and more than 100 other cities.

The campaign, known as “Fight for Fifteen,” refers to what many economists consider a “living wage” of $15 per hour – not even close to the $35 per hour that a Zillow analysis released last month reported that workers need to earn to afford a median priced housing rental in Denver.

The $35 an hour is more than four times the current minimum wage in Colorado, which increased to $8.23 an hour on Jan. 1.

Taking it farther

With the slogan “Low pay is not okay,” the effort by workers runs parallel to support for increasing the national minimum wage to $10 per hour.

Denver City Council members Susan Shepherd and Robin Kniech agree with Klawitter, telling Greater Park Hill News that they actually would like to take their support of workers a step farther.

“I believe very much that current wages (for low income workers) are completely inadequate,” said Shepherd. “Low pay restricts the ability to pay for essentials of life such as housing, food, child care, and transportation.”

Shepherd said she supports any kind of wage increase. “More money in the hands of workers means more money flowing into the local economy to support upward growth and momentum.”

Shepherd recently returned from a conference of city officials in New York City where, she says, wage rates were a prominent part of the discussions. In 2006, Shepherd led a campaign by the Denver Area Labor Federation for an increase in the Colorado minimum wage.

Said Kniech: “As elected officials, we should care about the wages paid in our city, because they have a direct impact on the ability of our residents to live independently and self-sufficiently.

“Where the private sector fails to pay a living wage, it isn’t only the families who suffer. Too often we as a community end up paying more for human services to make up for housing, child-care, and other costs that wages don’t cover.”

Corporate profits on the rise

Klawitter, the Park Hill clergyman whose denomination has a history of social involvement, notes, “We have more low-wage workers who live in poverty than any other rich, industrialized nation on the planet.

The fact that people are working and living in poverty should not be a point of pride for any American or person of faith,” he said.

While more workers fall into poverty, corporate profits have stayed at or near record highs, says Joe Thomas of Jobs with Justice in Denver.

“If we increase the income of low-wage workers, they will spend their money on essential items and help the economy to grow,” Thomas adds. “So we need to acknowledge that someone will always do the service jobs. We need to provide decent jobs with family-supporting pay and benefits.”

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the national poverty level is just under $24,000 per year for a family of four. That family would need combined earnings of $11.00 per hour to meet the poverty level, higher than the $10.10 minimum wage increase suggested by President Barack Obama and other political officials.

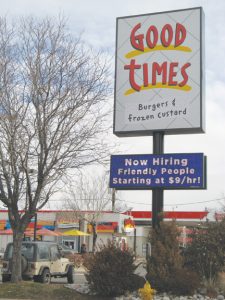

In Denver, “Help Wanted” notices at McDonald’s in Park Hill and at Good Times at Colfax and Colorado have posted starting wage at $8.75.

Currently, Colorado municipalities and counties cannot set their own minimum wage, however lawmakers will reportedly take that issue up during the legislative session that begins this month.

According to the latest figures from the Census Bureau, 13 percent of Colorado’s population is at or below the federal poverty level.

$15 in Seattle — eventually

Beyond Colorado, last June Seattle Mayor Ed Murray led the City Council in unanimous approval of a phased increase in minimum wage to $15 per hour. The decision followed the election of Socialist Councilwoman Kshama Sawant, and her call to improve the plight of low-income workers. Washington state minimum is $9.32.

In November, San Francisco voters approved Proposition J, increasing the minimum wage to $15 per hour by 2018. That city already has the nation’s highest hourly minimum at $10.74.

Minnesota has raised the state guaranteed wage to $9.50 by 2016. California, Connecticut, and Maryland also have laws increasing their minimums to $10.00 or more in the next few years.

The California chain that Denver Councilman Albus Brooks has been trying to get in Denver, In-n-Out Burgers, starts new associates at $10.50 an hour. The company posts a statement saying workers “are important to us … and our commitment to a higher starting wage is just one of the ways we show it.”

Some silence in Colorado

In Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper demurred during at least one gubernatorial debate last fall, when asked whether he’d support an increase in the minimum wage. Denver Mayor Michael B. Hancock has not articulated his position on the subject.

One notable operator of several Denver McDonald’s, Rose Andom, declined to comment for this story. Andom owns three franchises at Denver International Airport. She is also vice chair of the Black McDonald’s Operator’s Association. Tom Carlson Jr., who operates the McDonald’s on the 16th Street Mall, did not respond to requests for comment.

But in comments published in the Denver weekly Westword last year, Carlson defended what he pays his workers. “I don’t have anybody in the restaurant who makes minimum wage,” Carlson was quoted saying. “We do a really nice job in our organization with our employees. We provide a very competitive wage. I offer phenomenal benefits.”

In a CNBC interview broadcast last May, Subway founder and CEO Fred DeLuca said he believes wages should rise automatically with inflation.

“Over the years, I’ve seen so many of these wage increases, I think it’s normal,” said DeLuca. Subway has the most locations of any fast food chain, and DeLuca previously declared that increasing the minimum wage too quickly would be a bad idea, but that “workers deserve to make more.”

In late December, an ad for a Denver area Subway “sandwich artist” listed the starting wage at $9.76 an hour.

Other Denver-based companies – Good Times, Chipotle, and Boston Market – declined to comment for this story.