A Few Bloody Days Of August, 1920

On the heels of a pandemic, wide unemployment and anti-Black riots, Denver’s tramway strike and resulting madness a century ago can be explained as a kind of earthquake triggered by an over-stressed society.

By Stephen J. Leonard

Special to the GPHN

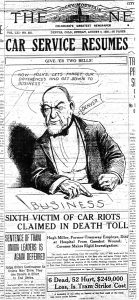

Seven people were killed and scores injured during a few bloody days in Denver in early August 1920. Three teenagers died in the mayhem of a tramway strike that spiraled out of control. Among those shot and injured were a 9-year-old boy and a 12-year-old girl.

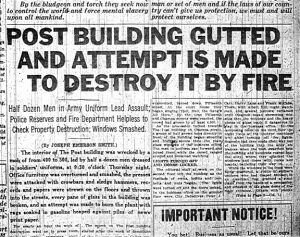

Rioters tore through downtown and tried to burn the offices of The Denver Post. The newspaper’s co-publisher Frederick G. Bonfils – one of Denver’s richest men and reputedly its most hated – took no chances. He posted guards with machine guns atop his mansion on the southeast corner of 10th Avenue and Humboldt Street near Cheesman Park. Surely they could beat back attackers.

The conflagration was largely sparked by the Denver Tramway Company (DTC), a transit monopoly vital to the city’s functioning. Owned by some of the city’s richest men, including Charles Boettcher and Gerald Hughes, company officials claimed that it had high expenses and hence could not raise wages. (Historian Phil Goodstein has since discovered that the DTC was turning a more than 4 percent profit.) City officials might have eased both the company’s and the workers’ problems by allowing a fare increase, but voters and politicians opposed that.

Tramway workers saw their purchasing power badly eroded by rampant World War I inflation. In a brief 1919 strike they won some concessions. In 1920 they hoped to do better. At 5:30 a.m. on Sunday, Aug. 1, 1920, drivers stopped manning the streetcars.

Riff-raff and petty criminals

Riff-raff and petty criminals

In 1919 DTC had been caught unprepared. In 1920, the company was ready. Even before the strike began, it hired “Black Jack” Jerome, a tough union buster. Jerome quickly imported hundreds of strike-breakers. The men were housed at the Tramway’s headquarters and car barns at 14th and Arapahoe, at the company’s barns near 400 S. Broadway, and at its East Side barns on 35th and Gilpin.

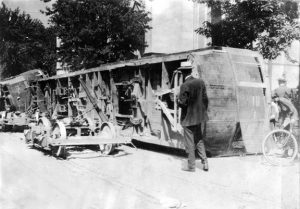

The strike-breakers, some of them riff-raff and petty criminals, some supposedly college students, would, DTC hoped, drive the cars and break the strike. To protect his men, he wrapped the trolleys in wire mesh and equipped them with canisters of carbonic acid mixed with soap – a fizzy, stinging, non-lethal concoction designed to discombobulate attackers.

The strike-breakers, some of them riff-raff and petty criminals, some supposedly college students, would, DTC hoped, drive the cars and break the strike. To protect his men, he wrapped the trolleys in wire mesh and equipped them with canisters of carbonic acid mixed with soap – a fizzy, stinging, non-lethal concoction designed to discombobulate attackers.

In a day when fewer than 15 percent of Denverites owned automobiles, and not many city dwellers had horses, people depended heavily on the Tramway’s fleet of electric trolley cars, which drew their power from overhead wires and ran on fixed tracks.

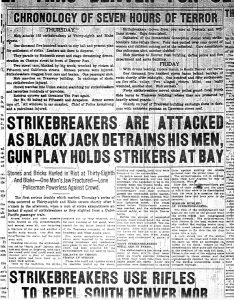

Churchgoers were inconvenienced on Sunday, but the real crunch came on Monday, when tens of thousands either had to walk to work, or, if lucky, snag an automobile ride. Strike-breakers ran only one car on Tuesday, Aug. 3. On Wednesday they scored a symbolic victory and collected six cents by picking up a paying passenger. On Thursday union leaders urged union members to avoid violence, of which there had been relatively little up to then.

Late Thursday afternoon Denver exploded as mobs surged through downtown. They attacked the Denver Post offices at 1544 Champa, partly because the Post supported the Tramway and partly because the newspaper had incurred the enmity of many. The mob failed to burn the building and the damage it did to the newspaper’s presses proved superficial.

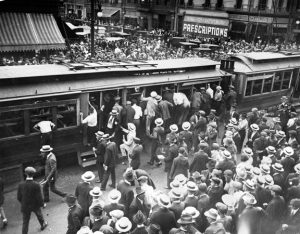

At 15th and California rioters attacked two streetcars. Seventeen people were injured. Others derailed four streetcars in front of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception at Colfax and Logan. Some strike-breakers escaped into the Cathedral, where one hid behind the altar. An unlucky one fled to a nearby apartment building, where he was caught and beaten senseless. A mob attacked the East Side barns and burned two tramway cars at 40th and Williams.

At 15th and California rioters attacked two streetcars. Seventeen people were injured. Others derailed four streetcars in front of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception at Colfax and Logan. Some strike-breakers escaped into the Cathedral, where one hid behind the altar. An unlucky one fled to a nearby apartment building, where he was caught and beaten senseless. A mob attacked the East Side barns and burned two tramway cars at 40th and Williams.

Police were powerless

Around 9 p.m., some members of a crowd – estimated at 10,000 – began pelting the Broadway barns with stones. Half an hour or so later some of the 126 strike-breakers fired into the crowd killing two 19-year-olds who were running away from the barns. Two others were injured.

Police, outnumbered by multiple mobs in different parts of the city, seemed powerless. Police Chief Hamilton Armstrong was felled by a brick and other officers were hurt. By Friday morning, two people had been killed and at least 33 injured.

On Friday, Denver mayor Dewey C. Bailey asked for volunteers to assist the police. Many World I veterans, members of the American Legion, responded.

The New York Times of Aug. 7, painted a chilling picture: “Downtown Denver is a heavily armed camp tonight [Aug. 6]. Armored tank cars, mounted with Browning machine guns capable of firing 500 shots a minute, are patrolling the streets.” The Times continued: “Many volunteers, private citizens who jumped into the breach . . . a number of whom have looked over No Man’s Land at German trenches, are carrying Enfield and Springfield rifles, lent to the city by authorities at Fort Logan.”

Shooting into the crowd

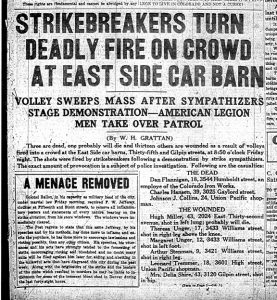

Fortunately the machine guns apparently were not deployed at the East Side barns that Friday evening, or the death toll might have been worse. There, a crowd taunted strike-breakers inside. When Jerome and others drove toward the barns at 9 p.m. someone in the crowd cried “Scabs!” Bricks hit the car’s radiator and smashed the windshield. Jerome’s men fired on the crowd, killing one instantly and hitting four others who died later.

Among the dead were a 16-year-old girl and a 19-year-old man. The wounded included a 9-year-old boy and a 12-year-old girl.

At 1:30 a.m. on Saturday, Aug. 7, Colorado Governor Oliver Shoup and Mayor Bailey asked the U.S. Army to take control of Denver. Two hundred and fifty troops from Fort Logan south of the city arrived quickly. Later 500 more came from Camp Funston, Kansas. They disarmed Jerome’s men and then protected them as they drove the cars. By the time the troops left on Sept. 8, Denver had, at least on the surface, more-or-less returned to normal.

At 1:30 a.m. on Saturday, Aug. 7, Colorado Governor Oliver Shoup and Mayor Bailey asked the U.S. Army to take control of Denver. Two hundred and fifty troops from Fort Logan south of the city arrived quickly. Later 500 more came from Camp Funston, Kansas. They disarmed Jerome’s men and then protected them as they drove the cars. By the time the troops left on Sept. 8, Denver had, at least on the surface, more-or-less returned to normal.

The aftermath

Given the deaths of more than a thousand Coloradans in World War I, the more than 7,700 killed in the state by the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919, high inflation, high unemployment, and the madness of anti-Black riots in various American cities in 1919, the Denver insanity of 1920 can perhaps be explained as a kind of earthquake triggered by an over-stressed society.

It is also plausible, even likely, that the spectacular rise in the early 1920s of Denver’s Ku Klux Klan, a white supremacist organization that stressed law and order, was partly a reaction to the mayhem of that bloody August of 1920.

The strike and many of the strikers were crushed; the union broken. The Tramway went bankrupt, but emerged from the process in 1925 a financially sounder company with little or nothing to fear from its thoroughly cowed workers.

Sources: Phil Goodstein, Robert Speer’s Denver 1904-1920 (2004) provides an excellent account of the origins, progress, and aftermath of the strike. Stephen J. Leonard treats the turmoil in the article “Bloody August: The Denver Tramway Strike of 1920,” Colorado Heritage (1995 Summer).

Park Hill resident Stephen J. Leonard is a professor of history at Metropolitan State University of Denver.